- Home

- Alex Irvine

Anthropocene Rag Page 3

Anthropocene Rag Read online

Page 3

He shut the unit back up and then opened his own box and took out the card. When he touched it, iridescent swirls played across its face against plain black words.

Greetings, Henry Dale! You may present this card at any entrance to MONUMENT CITY. Upon presentation, your entry to MONUMENT CITY will be guaranteed. This card will assist you in your travels. It is not transferable. The City looks forward to your arrival.

Warm regards,

Moses Barnum

Monument City?

He’d heard of it. People said it was some kind of paradise in the Rockies somewhere, or up in Minnesota, or out in Death Valley. They said that if you got too close, robots would come down out of the sky and kill you, or the ground itself would turn into monsters that would eat you, or that defense nanos would turn you into gray goo. They said that sometimes people got to go into Monument City, but nobody ever got to leave. They said that if you entered, you were transformed and became something other than human. They said it didn’t really exist, that it was a fever dream of a world in the middle of falling apart.

Henry Dale knew that anything could fall apart, anytime, with no warning. New York had done it once right before he was born, and he had grown up with the evidence of it all around him. The tsunami wasn’t the worst part. It had done its share of damage here and there, but mostly out on Long Island and in New Jersey. Everything over in Jersey was still a chemical soup of unknown bizarro horror twenty years later, thick with Boomlets drawn by the rich environment of hydrocarbons. He wasn’t going there.

That presented a problem for this ticket, or because of this ticket. Henry Dale tried to figure a way he could get from New York to wherever Monument City was—Montana? Utah? Saskatchewan?—without using either the Holland Tunnel or the Skyway. He would have to go north, to the GW or even the distant Tappan Zee. Through Westchester, where trigger-happy citizen militias kept an eye out for people coming out of the Bronx. Or he could try a ferry over to the Palisades, staying away from the real madness . . . but he didn’t know what he would find there, either.

Best thing to do would be drop this card in the nearest sewer and see if the hippo translated it into Chinese, not that Henry Dale would be able to tell. Forget about it, he told himself. How are you going to get two thousand miles by yourself?

Still. Monument City. Henry Dale felt the strange call to strike out into the unknown, and he knew it was crazy but he didn’t care. He could spend the rest of his life shuttling letters around the rectangle defined by Fourteenth and Twentieth Streets, First Avenue, and Avenue D . . . or he could get out. See what the world really had to offer.

Who had left the ticket? Henry had a feeling it was the strange old guy with the mustache who had passed through over the weekend. No concrete evidence, but definitely a feeling. That guy had definitely had a whiff of the Boom about him. Henry Dale had been out on his stoop listening to the playground and seen the guy walking past the sprinklers. “Hey, man,” he’d called out. “Stay away from those.”

The guy had chuckled. “Something in the water?”

“Yeah.” Henry couldn’t tell where the guy had come from.

“Well, I’ll steer clear, then,” the guy had said, but he hadn’t seemed too concerned. “You’re the mailman, right? Henry Dale?” He came over to the stoop and leaned on the railing, pushing his hat up on his forehead.

“That’s me,” Henry said. It was a bit surprising that a stranger would know him, but it happened. Henry didn’t get a bad feeling from the guy despite the twin holsters. People knew who the mailman was.

“Wonder if you’d mind posting this for me,” the old guy said, handing Henry an envelope.

Henry glanced at the address. Detroit. “Sure,” he said.

“How long you reckon it’ll take to get there?”

“A week or so, anyway,” Henry said. Cross-country mail averaged about a hundred miles a day, or so he was told. He’d toyed with the idea of joining the interstate postal service.

“That’s fine,” the guy said. “My name’s Ed. This your building?”

“Yeah,” Henry said.

“Nice place.”

Henry shrugged. “It’s all right.”

It was in fact one of the quieter and safer places to live in the city because the threat of the weirdness in the playground and the sprinklers kept people away. Some of the bigger parks were home to real strange wildlife, and even stranger people, and although there were plenty of places in Manhattan where life went on more or less as it always had, there were also areas where you didn’t go unless you wanted to be either dead or transformed into something no longer human.

“Well, I’m gonna shove off,” the old guy said. And he had, disappearing into the shadows around the corner of the building. Henry Dale hadn’t given him another thought until now, standing in the lobby of his building on a Monday afternoon when he should have been going to see Alicia but instead was contemplating something much grander.

He still had the letter to Detroit. He’d forgotten it over the weekend, but now that lapse in memory seemed like an omen. I could take it myself, he thought . . . and on the heels of that thought he wondered if maybe Ed had wanted exactly that. Henry looked at the letter again. It was addressed to one Mohamed Diaby, of Butternut Street. Well, he thought.

The City looks forward to your arrival.

Could a city do that? Or a City?

Maybe Monument City could.

Despite his piety Henry Dale was of that American strain that does not believe it can die even as the last hogshead of blood is leaking from its veins. So he had been told and he believed it although he did not know what it meant in a New York that had been scoured by tsunami and the tendrils of the Boom and the serial maladies and catastrophes attendant upon climate collapse, et cetera.

None of that mattered when a messenger appeared and revealed that God was still speaking. This was why the Boom had left him behind.

Pure fight was Henry Dale and it wasn’t until he had seen the ticket to Monument City that he had ever thought about it that way. But once he saw it there was no other way to see it, even if he was only seeing it that way because the ticket had done something to him. So be it, he thought. Might die in the desert. Might never make it past the Allegheny, or whatever it’s called. Might wander off into a nano-hallucination and be eaten by cannibals in Ohio.

Let’s find out.

And let’s stop in Detroit along the way and get this letter to Mohamed Diaby.

“All right, Monument City,” Henry Dale said. Outside the playground was talking and Henry Dale was thinking that one of these days he wanted to have children who could play on playgrounds that didn’t talk. “I’ll come find you. Don’t you hide from me when I do.”

The postal service would have to do without him for a while. He had a new Godswalk to pace off.

4

FLANKED BY TWO WOMEN who thoroughly intimidated him—his brother’s still-maybe-girlfriend Serena on the left, his fish-market coworker and secret crush Tonya on the right—Kyle Hendricks stood at the gates of JeebusLand and took three long, slow, deep breaths. “Reenie,” he said. “You sure about this?”

“What else are we going to do?” she said. “We owe him.”

She was right but Kyle was antsy and snappish. “Tonya owes him. She’s his niece.”

“Stay out here, then,” Tonya said. “We don’t need you.”

JeebusLand, the actual name of which was the Bible Truth Experience, had been around for a long time, and it showed. The lights were out, the parking lot was a jungle, and the parts of it you could see from the street looked decrepit. The peeling murals painted on its perimeter wall were like a cartoon tour of a deranged evangelist’s head. See Jesus ride a velociraptor! Eat a trilobite taco! The Boom had found places like theme parks especially interesting, and JeebusLand was no exception. All kinds of weird shit went down in there, and rumor had it that the most recent weirdness had created an actual living dinosaur. Whether this was

because the zealots who tried to keep the park going were also rogue geneticists, or because the Boom worked in mysterious ways, nobody seemed to know.

What they did know was that one of the rich old freaks in the gated lake sanctuary of Islesworth was offering a good bit of money and favor to whoever could come out of the park with this creature—or with proof that it was a fake. This same rich old freak, Hilario Gonzalez by name, employed both Kyle and Reenie, and Tonya was his niece. Also Hilario was about to die of some kind of awful wasting disease and had said it was his one remaining desire to see this dinosaur of JeebusLand, or at least video of it.

So into the park they would go. If it was a little dinosaur they would grab it and bring it to Hilario. If it was big they would shoot vid of it with a microrecorder Tonya had.

The front gate was always barred, closing off a plaza dominated by three crosses. For a while right after the Boom, the park’s leaders had crucified people there. Things had settled down enough since then that JeebusLand was just another address in the bizarre new Orlando. Except now more interesting again because there might be a dinosaur inside. And since Kyle and Reenie and Tonya were guessing that the park’s current owners wouldn’t want that dinosaur disappearing, they weren’t announcing themselves. Reenie knew another way into the park.

It was around to the east from the park’s main gate, backed up against train tracks and hidden at the base of a concrete wall designed to look like Jericho or Jerusalem or some other city from the Bible. Water trickled into a drainage ditch from a four-foot opening there. Once it had been barred, but the bars had rusted away and they could look into a tunnel that had a faint glow of daylight at the other end.

“They’ve got a pond in there,” Tonya said. “When it floods they pump the extra water out through here.” Along the southbound lanes of I-4, behind a decrepit hotel, were two holding ponds lined with egrets and alligators. Kyle figured the overflow must end up there. Maybe it sanctified the wildlife.

“Okay,” he said. “In we go.”

They stooped down and bear-walked through the short tunnel, coming up in a sluice channel behind the main auditorium where JeebusLand had once put on entertaining shows of whippings on the Via Dolorosa, trained lions pretending to eat mannequins of early Christians, that kind of thing. Ahead of them the channel led to a small lock at the edge of the pond. To their left loomed the auditorium. On the other side of the channel were various other exhibits, all neglected, rusting, and overgrown. Since the Boom, JeebusLand had become a retreat for zealots who wanted to watch the End Times from inside a cartoon Bible . . . which, come to think of it, wouldn’t be a bad way to spend the end of the world.

“So where’s it supposed to be?” he said quietly.

Reenie shrugged, brushing past him. Tonya went with her. All three of them skirted along the path that followed the contours of the pond. At intervals stood little kiosks with bits of pseudo-scientific gobbledygook about Noah’s ark and quantum theory. Jesus holds all things together . . .

“This is the Lord’s house,” a voice boomed from behind them.

They turned away from the pond and looked up at a raised area with semicircular ranks of benches facing a podium. Standing on one of the benches was a sixtyish white guy with a salt-and-pepper beard hanging down to his waist. He was wearing a brown robe and sandals and he held a single-barrel shotgun leveled right at Kyle’s belly button. “You are trespassing in the Lord’s house,” he said.

“We’ll leave,” Tonya said immediately.

“Oh, it’s too late for that,” he said. “I am the keeper of the flock and the gatherer of strays. You are strays, and now you are gathered.”

Kyle held his hands up and out. “Take it easy, man,” he said. “Like Tonya said, we’ll go.” He’d had a gun pointed at him before, but only once, and never by a deranged preacher dressed like he thought he was living in the book of Leviticus.

“No, you won’t. We’re pretty old-fashioned around here,” the preacher said. “We believe in sacrifice, and we believe in keeping ourselves sequestered. This is a holy place and you have defiled it. Simple as that.”

“I go to church,” Tonya said.

“Me, too,” Reenie added.

Kyle couldn’t bring himself to lie.

“Doesn’t matter,” the preacher said. “Going to church doesn’t make you holy. Orlando’s lousy with churches. Holy is as holy does. Now come on.” He twitched the barrel of the shotgun in the direction of the plaza inside the front gate.

“Come on where?”

“To the plaza out front. Three of you, three crosses. There’s a lesson to be learned and some sinners only learn one way.” The preacher’s face was grim. He thumbed back the hammer. “Now walk.”

Kyle took a step. Before they got there, he’d make a move. He’d jump the guy or something, wait for a chance. He couldn’t be planning to hang them all on crosses by himself. There would be other loonies. He caught Reenie’s eye, trying to telepathically say, Let’s get him while he’s still alone. Her face was blank but she had also taken a step with Kyle. He couldn’t see Tonya. She was behind him.

In the water, something moved. Kyle looked back. Reenie, too. Tonya, incredibly, went for her recorder. She scooted closer to the water’s edge and pointed the recorder at the swirl on the surface. A tiny spotlight next to its lens caught the outline of something. “Guys, look!” she shouted, as if there wasn’t a gun pointed in her direction. “It’s—”

What came out of the water looked a lot like a gator. Head like a narrow triangle, eyes set close by the hinge of wide-open jaws, rough scaly skin, long muscular tail driving it up and toward the light Tonya had unknowingly stuck in its face. But it had way too many legs, and Kyle could have sworn he saw it standing up on hind legs a lot longer than any gator’s. It clamped down on Tonya’s forearm and the light from the recorder shone in narrow split beams between its teeth.

Tonya screamed and pulled back but her feet went out from under her and she slid on her back into the shallows as the gator-thing hauled on her arm. It wasn’t quite as big as she was but it was much stronger. Kyle lunged and caught her by the hair with one hand, sprawling on his belly and hooking his other arm under her shoulder. That kept her head above the water. The recorder light went out under the water. Tonya kept screaming. Reenie had gotten her other arm and Kyle swung his legs around and dug his heels into the soft ground by the edge of the pond.

Then, as abruptly as it had attacked, the gator-thing let go. Kyle and Reenie fell over backward with Tonya landing partially on top of each of them. Her bitten arm stuck straight up in the air over Kyle, dripping blood into his eyes. “God Jesus fuck,” he said, closing his eyes and shaking his head. At the same time he was still trying to pull her farther from the water.

When they’d gotten her onto safe dry ground Tonya stopped screaming. Now she was looking at her arm with her mouth hanging open. From just below the elbow to the back of her hand was a series of ragged punctures and tears. Loose flaps of skin hung away from the deeper gashes. Kyle saw bone. He had her blood on his face, in his mouth, all over his clothes.

Tonya’s eyes rolled back in her head. Reenie slapped her. “No, you don’t,” she said. “Stay awake.”

The preacher watched, the barrel of his shotgun steady as a rock.

5

GECK AND PROSPECTOR ED reached Orlando three days later. After that initial burst of conversation, Ed hadn’t said more than three words at a stretch. He slowed down to Geck’s pace and even let Geck get a solid eight hours’ sleep each of the three nights. Geck slept more soundly than he had since getting to Miami, knowing that he had a nano-juiced bodyguard capable of killing anyone who might come by. The only time he woke up—or the only time he remembered waking up, anyway—was on the second night, when the mosquitoes were bad and their whining in his ears had him thrashing around. He sat up in the darkness and looked around. Ed wasn’t there. Geck almost called out, but if he didn’t know where Ed was, maybe it wa

sn’t smart to call attention to himself. He waited, wakeful and nervous, for what seemed like a long time.

When Ed appeared from the brush at the side of the road, Geck said, “Where’d you go?”

“Had an errand to run,” Ed said.

“An errand?” They were in the middle of nowhere. The last road sign had said Kenansville. “Where’d you run an errand out here?”

“None of your business,” Ed said. “Go to sleep.”

Geck thought of a hundred other questions, but before he could decide which of them to ask, he had fallen asleep. In the morning Ed wouldn’t say anything about it.

Now they were getting close to Orlando and Ed was asking him about where Kyle lived. “Last I knew he was staying in an old hotel by the airport,” Geck said. “Reenie was over there, too.”

“Reenie’s your girl, right?”

“I think so. I hope so,” Geck said. Now that he was about to see her again, he wasn’t too sure that she would be welcoming.

Orlando was still pretty civilized, unlike Miami. The freeways were mostly empty, but on the surface streets there was traffic. Mostly buses and old rebuilt cars. Once in a while you saw a custom-built car, sleek and shiny, belonging to one of Orlando’s upper-crust families who stayed gated off in the old rich neighborhoods. Geck had once tried to sneak into Islesworth on a dare, back when he was about fifteen. It was the first time in his life he’d been shot at.

Past the old interchange between the turnpike and the ring road that went around east toward the airport, at the loop where Orange Blossom Trail went by, an old school bus, the short kind, sat farting biodiesel smoke in a parking lot. RODOLFO! was hand-painted in bright blue letters on its side. “Right there,” Geck said, pointing. “The Dolf goes to the airport.”

“We’re not going to the airport,” Ed said.

“I just told you, ese, that’s where Kyle and Reenie live.”

Marvel Novels--X-Men

Marvel Novels--X-Men Tom Clancy's the Division

Tom Clancy's the Division Pacific Rim: The Official Movie Novelization

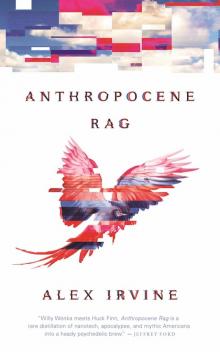

Pacific Rim: The Official Movie Novelization Anthropocene Rag

Anthropocene Rag Black Lagoon

Black Lagoon Phase One: The Incredible Hulk

Phase One: The Incredible Hulk Phase One: Iron Man

Phase One: Iron Man Pacific Rim

Pacific Rim Pacific Rim Uprising--Official Movie Novelization

Pacific Rim Uprising--Official Movie Novelization Phase Three: Marvel's Captain America: Civil War

Phase Three: Marvel's Captain America: Civil War Phase One: Thor

Phase One: Thor Dawn of the Planet of the Apes: The Official Movie Novelization

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes: The Official Movie Novelization Phase One: Marvel's The Avengers

Phase One: Marvel's The Avengers Phase One: Captain America

Phase One: Captain America Exiles

Exiles The Seal of Karga Kul: A Dungeons & Dragons Novel

The Seal of Karga Kul: A Dungeons & Dragons Novel Marvel's Ant-Man - Phase Two

Marvel's Ant-Man - Phase Two The seal of Karga Kul (dungeons and dragons)

The seal of Karga Kul (dungeons and dragons) Mare Ultima

Mare Ultima Phase Three: MARVEL's Doctor Strange

Phase Three: MARVEL's Doctor Strange MARVEL SUPER HEROES SECRET WARS

MARVEL SUPER HEROES SECRET WARS Phase Three: MARVEL's Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2

Phase Three: MARVEL's Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 Dawn of the Planet of the Apes

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes Independence Day: Resurgence: The Official Movie Novelization

Independence Day: Resurgence: The Official Movie Novelization