- Home

- Alex Irvine

Anthropocene Rag Page 2

Anthropocene Rag Read online

Page 2

Right now he was watching a crime and considering how weird it was to think of crime. For there to be crime, there had to be laws, right? And in Miami it had been a long time since there were laws.

Out on the street an old guy in a cowboy hat was in the middle of being shaken down by two of Double Louie’s crew. Geck had an interest in this not because he cared about Double Louie, who was someone Geck avoided just like he avoided the people on the top floors of this office tower, but because he’d heard that the old guy had been asking around after Geck’s twin brother, Kyle. Geck and Kyle weren’t real close—in fact, Kyle was in Orlando, which meant they weren’t close at all, ha-ha—but Geck still wanted to know who the old guy was and why he was looking for Kyle.

Double Louie’s goons were getting aggressive. One of them reached out and poked the old guy in the chest. The old guy gave an aw-shucks dip of his head and said something. He was dressed up like some kind of actor in a Wild West show, complete with six-guns and a fringed leather jacket. He carried a leather satchel slung from one shoulder to the other hip. Geck couldn’t see his feet because the old guy and Double Louie’s goons were standing in knee-deep water, but he guessed the old guy was wearing cowboy boots, too. The second goon got in the old guy’s face and showed him a knife. The old guy took a step back. The first goon went to grab the satchel.

A flash of light blinded Geck. He ducked away from the window. His kayak was pulled up under the building overhang outside. If Double Louie’s goons spotted it, they would come looking for whoever it belonged to. Bad news. Geck debated leaving it, but couldn’t bring himself to do it. He took a deep breath and when no more flashes came, he peeked again. The old guy was walking away down the street like nothing had ever happened. In the swirling shallows behind him, two bodies floated facedown.

Geck went through the door and waited under the overhang until the old guy was farther away down the block. Then, before anyone else could claim the prize, he ran out into the pounding rain and splashed across the street to see what he could find on the bodies.

He came up with a double handful of coins, a gun with four shells in the magazine, a nice pair of waterproof shoes . . . and, after some feeling around on the submerged sidewalk, the knife. It was a combat model, one of the ones with a hollow handle that probably had fishing line or something in it. The blade was a good six inches, serrated along the back. Geck was happier about it than the gun, but he took everything.

Not bad. He looked in the direction the old guy had gone. He was still barely visible, walking west down the broad avenue. What had he done to these two guys? Geck smelled opportunity. Also danger, since Double Louie had eyes everywhere, and some of those eyes were doubtless watching Geck pick over the bodies of two of Double Louie’s goons. Might be time to get out of Miami for a while, especially since he had some traveling money now. The quarters and Susies he had were more than enough to buy a bus ride to Orlando.

Geck made space for his new loot in his pockets by throwing away older, inferior loot. Then he splashed back to his kayak and paddled after the old guy, keeping enough distance between them that the old guy wouldn’t have any reason to look back.

As he paddled inland, Geck realized he didn’t really have any reason to look back, either. His girl was in Orlando, his brother was there, too. He’d come down to Miami to do a little prospecting and a year later he had nothing to show for it but the kayak. Well, and the stuff he’d taken from Double Louie’s dead goons. Miami sucked. It was all pythons and gangsters and collapsing buildings. Time for Geck to get back to dry land. Whatever the rising oceans had started here, Cumbre Vieja had finished.

Cumbre Vieja, Cumbre Vieja, Cumbre Vieja. People down here said those words like a spell. Geck didn’t even really know what it was. An island somewhere, he’d heard. A volcano that erupted and the waves from it had come all the way across the ocean to flood New York and Boston and Washington. Geck had never been to any of those places, but he’d seen the remains of the Florida coast cities north of Miami—which had been spared the worst of the tsunami. Daytona? Swept clean. Sand and rubble and bodies tangled in seaweed for the gulls to pick. West Palm? Not much better. But Miami, so hard-hit by the rising oceans and hurricane after hurricane after fucking hurricane? The tsunami had gone easy there because the Bahamas had broken its march across the Atlantic. Small mercy for Dade County, tough luck for the Bahamians. Even without the tsunami, things were still shitty in Miami, though.

The story was that he’d been born the night the waves came ashore, which was now twenty years and three weeks ago. He was an infant as the poisons spread up from Turkey Point and the nanos ate the poisons, turning them into something new. But who told the story and to whom, and whether the story had ever been meant to be believed, Geck Orlando did not know. He’d taken his surname from the town where he’d grown up. His parents were long gone. What did he know about truth?

* * *

He followed the old guy all the way to Orlando, which could have been hard but he caught some breaks. First, the old guy walked the whole way, ambling steady as a metronome up I-95 while Geck trailed him in the flooded ditches. Geck never knew when he was going to turn off, and he couldn’t go without sleep himself, so he had to come up with a plan. Two options presented themselves. One, he could sneak around the old guy and get ahead of him, then take the time to sleep while the old guy was catching up. Problem was, if the old guy turned off 95, or the Turnpike once it cut away from the coast to Orlando, Geck would never know it.

Two, he could approach the old guy and figure out some way to con him into letting Geck stick with him. The obvious downside to this plan was that the old guy might zap him dead, but Geck knew how to come across as nonthreatening. He was only twenty, and skinny. He didn’t look like much of a menace, especially to someone who had some kind of secret lethal zap gun.

Considering the situation, Geck decided he’d take the direct approach. They were somewhere inland from Fort Lauderdale when he made his move, and push was coming to shove because pretty soon they’d be on higher ground and Geck would have to leave the kayak anyway. He’d gotten around the old guy by paddling fast through a swamp that had once been an orange grove and then slogging back to the roadside, chopping himself up on the sawgrass all the way. His legs and forearms stung like hell, but that didn’t hurt nearly as bad as abandoning his kayak back there in the brush. He knew he would never see it again.

“Hey, mister,” he called out when the old guy got close.

The old guy stopped and looked down at Geck, who was sitting so the sawgrass scratches were displayed to full advantage. “What’s your trouble, son?”

“I’m lost,” Geck said. “I ran away and I need to get . . .” He wasn’t sure what to say next. “I need to get away. Where you going?”

“Orlando,” the old guy said.

Right, Geck thought. “Orlando?” he repeated with a big fake smile. “My brother lives there! Can I stick with you until you get there? I don’t want to go by myself.”

“Son, you’re not telling me the whole story,” the old guy said. His eyes gleamed under the brim of his hat. Uh-oh, Geck thought. That kind of gleam meant only one thing. The old guy was part Boom.

“Um,” Geck said.

“Your brother is Kyle,” the old guy said.

Geck had learned a long time ago that the best way to keep a lie going was to admit some truths along the way and fold them in so they fit. “Yeah,” he said.

“Well,” the old guy said. After a pause he added, “Okay then. Let’s go.”

Geck stood, but that gleam in the old guy’s eyes had him feeling real nervous. Maybe he should have stayed in Miami. Double Louie might have killed him, but in Geck’s world guys like Double Louie were known quantities. Old guys walking from Miami to Orlando with Boom-gleam in their eyes . . . that was something else. Shit, Geck thought. What did I get myself into?

And what did this guy (construct?) want with Kyle?

He walked, not

knowing what else do to. Maybe he could break away from the old guy when they were getting close, in Kissimmee or someplace, and find Kyle before the old guy did. “How’d you know Kyle was in Orlando?” Geck asked after a while. “I mean, if you were looking for him in Miami.”

“I got some bad information,” the old guy said. “Name’s Ed. Yours?”

“Geck.”

“Geck?” Ed looked sideways at Geck. “Your mama call you that?”

“I don’t know,” Geck said. “She wasn’t around.”

Ed clicked his tongue. “Hard way to grow up,” he said. “You got your brother, anyway.”

“And Reenie,” Geck said. “She’s my girl.” He thought it was probably still true. Serena Green. She had cried when Geck went to Miami, but they’d made each other promises. And Kyle had said he’d take care of her, not that Reenie usually needed much taking care of. She was a lot smarter than Geck was when it came to scoping out trouble.

“Can’t help but notice you got quiet there,” Ed said.

“Just hoping Reenie’s still around. I mean, you know. Around for me,” Geck said, seeing no reason to shade the truth.

“She say she would be?”

“Yeah.”

“Well, you can usually trust a woman more than a man when it comes to the heart,” said Ed. “At least that’s been my sense of it. But the other thing is, you can’t trust either of ’em worth a damn.”

3

HENRY DALE PACED OFF the Godswalk every morning, to purify himself and prepare for the day. His devotion calmed him but did not make him happy. He did not give much thought to happiness. Instead he focused on joy and peace, believing that if he could inhabit those states of grace they would synthesize themselves into happiness. If not, perhaps he did not deserve to be happy. That fear drove his devotional walks, from the Meat Garden up over the flooded streets and empty towers past the Hudson Yards Lagoon and at last to the Temple of Shattered Glass. Along the way were constructs and penitents, castoffs and flotsam both human and other. Henry Dale believed some of them to be divine manifestations taking the form of the Boom. All whispered the Catechism: First the Synception, then the Boom. First the Six, then Seven.

A rail car breached, rolled over, sank back into the lagoon. In the churning water fish flashed, gnawing at the rust on its undercarriage. Henry Dale walked on, picked up a shard of glass as he did every morning, added it to a cairn on the part of the Godswalk closest to the river, where he could imagine the sunset refracting through it. He never set foot on the Godswalk in the evening.

After his devotional he went to the post office and gathered the mail he was to deliver. For every piece of mail he was entitled to a certain number of calories, subject to certain minimum and maximum disbursements. Henry Dale had never needed the minimum, but had run into the maximum a couple of times, usually around Christmas. The Boomlet that ran mail in the city was cagey about the exact formula, but overall it worked for Henry Dale. Usually he had enough extra calories that he could trade them for clothes or electricity or whatever. Sometimes he gave them away. Charity was important in a world of suffering.

His usual delivery territory encompassed a chunk of Manhattan from Gramercy to Stuyvesant Town, where he lived. He’d never meant to be a mailman—in the orphanage they’d trained him in welding and plumbing—but the occult brilliance of the idea that you could give someone a letter and trust that there was a way to get it anywhere in the United States (if that place still existed) or the world (maybe) . . . well, that seduced Henry Dale the minute he learned of it. He wanted to be part of something like that, a sorcery or alchemy of trust and commitment. It fit with his impulse toward faith in the unseen.

Of course being a mailman also meant he had to be out in all kinds of weather. That was why he always paced off the Godswalk. If the weather was fine, it put him in a good mood before work. If the weather was bad, the Godswalk inured him to the misery of the shift that would follow. Henry Dale tried not to get too high or too low. The other reason he paced the Godswalk was for perspective. The Boom had not chosen him. He was normal in every way, remaining on the earth after the closest thing Earth had ever seen to a Rapture. He believed this was because the Boom loved mail as much as he did, so it tended to protect mail carriers. Tended to. Its caprices meant it could never be predicted.

Considering his origins—orphaned at the age of two by the Big Wave—Henry Dale felt pretty good about the life he was able to live. He had a dry place to stay, a stable method of getting the food he needed, even a girlfriend named Alicia whose father was a baker. He was about to turn twenty and all things considered, he felt that God had looked out for him so far. The ache of loss from his parents’ death was always there, but it was more of a sadness that he would never know certain things than a genuine mourning for something he had lost. He had no memories of them. They were names on paperwork that had survived the Wave and the Synception. If you’re going to be orphaned, Henry had said to Alicia’s parents once, when they were talking obliviously about the importance of family to survive these times—and then fallen into a paralytic embarrassed silence—if you’re going to be orphaned, two years old is the time to do it. Gives you lots of time to gather a surrogate family.

Right, ha-ha, Alicia’s dad had said. Now Henry Dale had the feeling they resented him for trying to rescue them from their mistake, because in doing so he had implicitly told them he was conscious of it, and understood it as something that needed forgiving. Therefore they felt blamed by the act of his absolution, as a result of which Henry Dale was fairly certain he wouldn’t be seeing Alicia much longer. She wouldn’t cross her parents. Neither faith—like Henry Dale, Alicia’s family were New Nazarenes—nor family background would permit it.

He respected that. He would keep pacing off the Godswalk and the Lord would guide him to another woman.

All this was on his mind as he loaded the mail into an old Schwinn bike trailer and pedaled off across town on Twenty-Third Street, cutting down First Avenue to Twentieth, where his territory began. He went through his route, west to east, finishing near the old power station on Fourteenth and Avenue D. His father had been an engineer there. His mother had been a researcher at NYU. That’s what people told him, and Henry Dale had no reason not to believe it. Pedaling back on Fourteenth with the empty trailer clacking behind him, he turned into Stuyvesant Town and wound his way through the paths to his building. It faced Twentieth Street but he lived at the back, with windows that looked across the access road to the playground.

Which was talking again, the voices coming through his open windows louder than they should have. Henry Dale knew what would happen next. Henry Dale, child of apocalypse, offspring of two human endings, denizen of the lost parts of a lost city . . . he knew what was going on when the playground started to talk. “Shut up,” he said out his window in the direction of the playground. But not too loudly. Once he had gotten the playground’s attention, and he didn’t want that to happen again.

In syncopation with the playground’s muttering, jets of water shot up from the fenced-off water play area next to it. Something had gotten into the water and now the sprinklers didn’t come on or off according to their old pattern. Henry Dale had played in them when he was little, but stopped when the playground found its voice. Voices. As an adolescent he’d gotten a little mystical and become convinced that part of the spirit of Cumbre Vieja was in the playground, having roared up through the Narrows and then remained behind when the waves receded. That and the Boom had done something to the whole area. People who got wet in the sprinklers . . . well, a lot of different things happened to them sometimes. The open spaces of Stuyvesant Town were full of weirdly transformed squirrels and birds. Rats, too. The Lord worked in mysterious ways.

The worst of it was always the playground talking, though. Man, did Henry Dale hate that. The hippo rocking back and forth on its spring shouted in Chinese at the turtle and the horse on the other side of the swing set. The horse never answered

and the turtle spoke only Spanish. Of all the playground fixtures, the only one speaking English—the only language Henry Dale knew—was the bear on the jungle gym.

Sometimes when the bear talked to him, Henry Dale wondered if he had gotten into the sprinklers by accident and then forgotten about it.

Never mind, he told himself. This was all familiar. He’d lived here all his life. Even so, it was hard to live in New York—or, he imagined, anywhere in such bizarre times—and not view your surroundings with a bit of superstition.

He drew the bedroom curtains so he wouldn’t be able to look at the playground anymore. Then he washed his face. He’d shaved his head a week ago, so he didn’t have to deal with hair. A damp cloth over his scalp freshened him up a little and he was ready to go meet Alicia for dinner. Picking up his keys from the table by the door, he went out and down the stairs into the lobby. It was bright outside. The day had gotten hot.

Pausing before he went outside, Henry saw something strange, a faint glow coming from the bank of mailboxes in the lobby. That was weird. He had just put mail in those boxes—the three of them still in use—and he hadn’t noticed any glow. He looked more closely and got a squirrelly feeling in the pit of his stomach. The glow looked like it was coming from his mailbox, 303.

He had not delivered himself any mail.

Who else had keys? Nobody that he knew of. Henry Dale held a hand close to his mailbox and felt no heat. The glow was a soft white. He thought for a minute and then he got out his keys and used the master to open the front of the cluster box. Most of the boxes were empty. The others had stuff in them that he’d delivered on Friday. The collection box had about a dozen pieces in it. And in his box lay a small card, faintly glowing.

He bent to look at it. There was writing on the visible side. He wondered if it had something to do with the playground talking, or if he was hallucinating from the water. Then he decided he was being stupid. “Well,” he said to nobody but himself. “It’s not gonna take itself out.”

Marvel Novels--X-Men

Marvel Novels--X-Men Tom Clancy's the Division

Tom Clancy's the Division Pacific Rim: The Official Movie Novelization

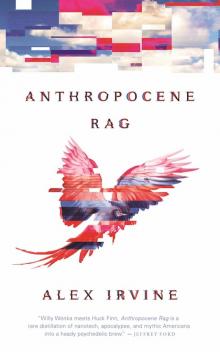

Pacific Rim: The Official Movie Novelization Anthropocene Rag

Anthropocene Rag Black Lagoon

Black Lagoon Phase One: The Incredible Hulk

Phase One: The Incredible Hulk Phase One: Iron Man

Phase One: Iron Man Pacific Rim

Pacific Rim Pacific Rim Uprising--Official Movie Novelization

Pacific Rim Uprising--Official Movie Novelization Phase Three: Marvel's Captain America: Civil War

Phase Three: Marvel's Captain America: Civil War Phase One: Thor

Phase One: Thor Dawn of the Planet of the Apes: The Official Movie Novelization

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes: The Official Movie Novelization Phase One: Marvel's The Avengers

Phase One: Marvel's The Avengers Phase One: Captain America

Phase One: Captain America Exiles

Exiles The Seal of Karga Kul: A Dungeons & Dragons Novel

The Seal of Karga Kul: A Dungeons & Dragons Novel Marvel's Ant-Man - Phase Two

Marvel's Ant-Man - Phase Two The seal of Karga Kul (dungeons and dragons)

The seal of Karga Kul (dungeons and dragons) Mare Ultima

Mare Ultima Phase Three: MARVEL's Doctor Strange

Phase Three: MARVEL's Doctor Strange MARVEL SUPER HEROES SECRET WARS

MARVEL SUPER HEROES SECRET WARS Phase Three: MARVEL's Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2

Phase Three: MARVEL's Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 Dawn of the Planet of the Apes

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes Independence Day: Resurgence: The Official Movie Novelization

Independence Day: Resurgence: The Official Movie Novelization