- Home

- Alex Irvine

The seal of Karga Kul (dungeons and dragons) Page 12

The seal of Karga Kul (dungeons and dragons) Read online

Page 12

On the ground, the swordwraith’s blade flashed out to strike an unwary Kithri, who was striking flint over another torch-but with a clang, Keverel flung out his mace at the last moment, deflecting the blow. His protective blessing wavered and the swordwraith turned on him, slashing open his mail shirt and the flesh underneath.

Her torch lit, Kithri swung it around and swept it through the denser shadow of the swordwraith’s head. The flame bloomed up and down its body and its screech pierced the night, spurred to a higher pitch when a leaping Paelias landed next to the prone Keverel and dispatched it with a stroke of his sword.

All of them looked up at Biri-Daar then, as she drew a deep breath and put her beaked mouth to the blackroot treant’s ear.

She did not want to use fire. She did not want to burn the forest or destroy the spirits that lived therein. But she did very much want this blackroot treant to find death, to return to the soil that had given it life. All of that time spent with elves and rangers had made her too sensitive, no doubt-but whatever the cause, when Biri-Daar unleashed her dragonbreath into the knothole at the side of the blackroot’s head, she did so with more pity than anger.

Flames flared out through the great rotting holes of its eyes and mouth, roaring along with the agonized roar the blackroot made. Blindly it grasped at Biri-Daar, found her, flung her away into the trees-but too late, as the flames caught the dead leaves of its crown and exploded into a great mushroom of fire. The roots holding Remy spasmed, twisted, and fell limp. Kithri sawed them away from his legs with a knife. “Lucan! Paelias! Find Biri-Daar!” she yelled over the sound of the flames.

In the last moments of its undeath, the blackroot staggered back toward the forest where its roots had first found sustenance. Then, Remy saw, it caught itself, jerking back from the edge of the forest in a shower of embers. Turning, losing its balance as the life burned out of its long-dead heartwood, the blackroot took one great step-over him, over the moaning Keverel, over Kithri-onto the Crow Road. And when it had gotten both feet on the road, it fell, its roots and branches dying by inches, curling and blackening as the flames found every inch of what centuries before had been one of the noblest beings of the world.

“Did you see that?” Lucan said wonderingly. “It moved out of the trees.”

Kneeling over Keverel, Kithri said, “Lucan, don’t be an idiot. It was undead. It didn’t know where it was going.”

“You believe what you believe,” Lucan said. He looked over at Paelias, whose chiseled face bore the same expression of disbelief as his own. Both of them looked at Remy.

“I think I saw it too,” Remy said. “It stopped and turned around, didn’t it?”

“Go find Biri-Daar!” Kithri screamed. “Go!”

They went, not wanting to argue, even though they were fairly sure that Biri-Daar was all right. She had survived far worse than a short flight through tree branches.

And they were very sure that they had seen that night something that none of them might ever see again: an undead creature remembering, at the moment of its death, something of its long-gone living self.

Neither Lucan nor Paelias said anything about this as Biri-Daar limped out of the darkness before they had gotten a hundred paces away from the road. They fell into step with her, waiting to see if she needed help. She waved them away. “Sore is all,” she said. “I am tempted to believe that the other trees… treants, perhaps, but perhaps just trees… I am tempted to believe that they looked after me a little.”

“I believe it,” Lucan said. “After what I saw that blackroot do, I can believe anything.”

That night they were able to sleep a little, in the lee of a grassy knoll far enough from the road that the crows wouldn’t follow them all the way. “How much farther are we on this road?” Paelias asked. “Which of you have traveled it all the way?”

“All the way? None of us,” Lucan said. “I have been on part of it.”

“I too. As far as the Crow’s Foot at the Tomb Fork,” Biri-Daar said.

Paelias looked around. “Just the two of you,” he said. “And neither as far as this Inverted Keep. Interesting. Well, I’ll take the first watch and perhaps in the morning one of the crows will bring us a map.”

In the morning, while they brewed tea and toasted bread, Remy said, “Would the crows do that? I mean guide us.” Keverel was slicing jerked meat. He paused and looked at Lucan.

“Interesting,” he said. “Would they?”

Lucan chuckled. “My guess is that I have no idea. I’ll give it a try.”

They waited as Lucan walked closer to the road and whistled out to the crows. Two of them flapped down into a dead tree closer to him. Remy watched as the crows bobbed their heads at Lucan. He pointed down the road, made a circular motion in the direction of the sun. After a few minutes, the crows flew back to their stations at the tops of the nearest trees. Lucan walked back toward the camp and the crows began to caw.

“They’re just sentries,” he said. “They’re descended, or say they are, from the crows buried along this part of the road, which according to them originally came from a clan that lived on the edge of the elves’ forest near the Gorge of Noon. Who knows whether it’s true.

“But they also said that they thought it was five more days to the Crow’s Foot, and a day after that to the Inverted Keep. I’m not sure how clear their ideas are about how far we can go in a day.”

“Not far enough,” Kithri sighed. “Is there water on the way?”

“Odd you should mention that. The crows said that the last day or so of the trek would be through a swamp.” Lucan squatted by the fire and poured tea. “They don’t like the swamp. They wouldn’t say why, but it was clear they didn’t like the swamp at all.”

“Well, I love swamps,” Paelias said brightly.

Keverel snorted. “Gods,” Kithri said. “You made the cleric laugh. Either this will be a great day or we will all die.”

Saddled up and back on the road, they watched the crows watch them for that day and the next. The Crow Road leveled out and traversed a broad landscape of naked granite and clear water, punctuated occasionally by twisted pines festooned with observant crows. “So,” Remy said when they had ridden the entire day without incident. “I’m starting to feel unusual because nothing has happened.”

“You mean nobody besieging us because they want your box?” Kithri said.

“Or undead spirits wanting to drag us down below the stones, to transform us into ghouls and wights.” Keverel smiled thinly. There had been too much of that in the reality of their days for it to carry much humor.

“When we get to the Inverted Keep, what are we going to find?” Remy asked.

“I don’t know.” Biri-Daar looked at the clouds gathering to the northeast. “I’ve never seen it except from the other side of the Whitefall. And I have never spoken to anyone who has been in the Keep and returned.”

“What do you know?” Paelias. “Every time someone asks you something, O dragonborn leader, you tell us what you don’t know.”

“What do I know?” Biri-Daar repeated. “I know that the Inverted Keep hangs hundreds of feet in the air over the Whitefall, and that the way into it involves a way underground through the tomb of the Road-builder. I know that he transformed himself in some way, and presides over the Keep as he has done for centuries. I know that…” She faltered.

They rode in silence until she was ready to speak again.

“I know that there is a dragonborn there. One of my ancestors,” Biri-Daar said quietly. “I know that one of the Guardians of the Quill is there. That…” Again she trailed off and again she mastered herself. “That will not be so once we have come and gone.”

None of them knew what to say. Remy watched the dragonborn who had led them this far, and he understood more about how and why she did what she did.

“I will find Moidan’s Quill, and bring it out, and we will take the quill to Karga Kul,” Biri-Daar said. She said it to the sky but meant them to

hear it. “The Mage Trust of Karga Kul will use the quill to reinscribe the seal and replenish its power. There are too few points of light in the world,” Biri-Daar went on, and her voice broke. “Karga Kul is one of them. It is also my home though I have not been there in many years. I would not have it drown in the chaos of the Abyss.”

If someone had asked him to list five things he thought he would never see, Remy would have put seeing a dragonborn cry high on the list. And he would have put tears from Biri-Daar at the top of any list. The paladin cried silently and without motion, riding forward with no change in her pace or expression. “It occurs to me,” Lucan said, “that if all of us chose to bear the sins of our ancestors, we would surely be suicides.”

“I fear that I can disagree. My ancestors have pledged themselves to Erathis for as long as there are records in Toradan,” Keverel said.

“Surely we don’t have to remind the good cleric that holy men sin,” Kithri said. “If we do have to remind him, I know some songs.”

“I don’t think so,” Keverel said, but once Kithri got started with a song, there was no stopping her.

Here I am, Remy thought periodically over the next few days of riding. I am with a group of strangers on a quest that means little to me. Why did they insist I come with them? Why didn’t they leave me at the market?

The box that had caused all the trouble was a foot long, give or take, and perhaps three inches wide and two deep. Its clasp was pewter and the seam between its lid and the box was invisible-unless magical attention was directed at it. The seam had glowed right along with the sigils on its lid when Iriani had first investigated the box. Remy wondered again what would happen if he opened it. It had been some time since anyone or anything had tried to take it from him.

What did Philomen want? Was Biri-Daar right that the vizier was untrustworthy, that he had sent Remy out into the wastes to die? Biri-Daar’s theory was that Philomen needed the object Remy carried to disappear because other forces in Avankil wanted it. Or that Remy was never intended to survive the trip to Toradan, and that after his death some agent of the vizier’s would have found his body and recovered the box.

No one in the group seemed to have any patience for the idea that Remy had been intended to deliver the box to Toradan.

“Who were you supposed to speak to there?” Biri-Daar asked on their fourth day. The Crow Road switchbacked down a steep slope for as far as they could see in front of them before disappearing into what looked like a lowland jungle. They weren’t in the lowlands yet, but before they got to the Whitefall there would be a good deal of marsh to traverse. Biri-Daar remembered that much of her previous passage along the road.

“I was given a place,” Remy said. “The vizier told me that when I arrived at Toradan, I should find the Monastery of the Cliff and speak to the abbot. But he never told me the abbot’s name.”

“The Monastery of the Cliff,” Biri-Daar echoed. “What would those monks want with a package from the vizier of Avankil?” She clucked her tongue, something that Remy had learned meant she was mulling a problem with no obvious solution. “You were sent out into the desert to die, Remy,” she said shortly. “That is clear to you now, isn’t it?”

“I know it’s clear to you,” Remy said. “That’s why I came along. But I still don’t understand… I don’t know anything. What does any of this Karga Kul business have to do with me?”

“The Abyss pursues you. And demons threaten Karga Kul,” Biri-Daar said quietly. “Do you want to stake your life on that being a coincidence? I would sooner cut my own throat than deliver an unknown, magically guarded item to the monks on the cliff.”

“Why?”

“It has been long years since those monks kept their holy orders,” Biri-Daar said.

They rode in silence for some time after that. Eventually Remy worked up his nerve and said, “Biri-Daar. This is a personal quest for you.”

The dragonborn nodded.

“Almost an obsession.”

Biri-Daar made no response.

“Perhaps your obsession is making it seem like my errand has something to do with your quest,” Remy said. “I don’t see it.”

“Would you like to turn around and go home now, Remy?” Biri-Daar asked.

Yes, Remy wanted to say. I would like to turn around and go home and forget that any of this ever happened…

Except that wasn’t true. All his life he had dreamed of adventure. He had looked at the ships docked in Quayside and imagined going all the places they had gone… all the places his father had gone. Remy had insatiably devoured every tale of heroism and magic, of questing and exploration, that he could find. He had learned to read solely so he could follow the stories told in the one book his mother had-her great-uncle’s memoirs about his time at sea in the waters far beyond the Dragondown Coast, waters beset with floating ice or great mats of living vines that grew up from the depths to ensnare and destroy unwary mariners…

He had memorized the names of every city and town on the coast and determined to visit each and every one, swearing to himself that he would make his name in the world and leave behind stories that other men would write.

“No,” he said to Biri-Daar. “I don’t want to go home.”

“Wise,” said the paladin.

“We both know I can’t go home anyway. It’s not wise to accept that which cannot be changed.”

“Perhaps not,” Biri-Daar said. “But it is certainly unwise not to. You are good company, Remy. And you have the makings of a fine warrior, it seems to me. But you are with us because… I must be honest here. You are with us because I trust nothing that has any taint of the vizier,” Biri-Daar said. “And that includes you.”

The Crow Road wound like a snake through swamp and jungle after descending along the flanks of the last northeastern range of the Draco Serrata. The earth itself turned first to mud and then seemingly to a slippery tangle of root and rotten leaf, as if they walked on a pad of floating plant matter under which there was nothing but dark water all the way to the center of the earth. That was what it felt like when the skies lowered, and through the midday semidarkness they tried to keep to the road, feeling its algae-slicked stones under their feet until inevitably they stepped off and began to slide into the depthless muck. Biri-Daar nearly roped them all together, but at the last minute thought better of it; the threat was a little too real that they might all be reeled downward like a stringer of fish.

“Hey, Lucan, what do the crows have to say?” Kithri asked on their second day out of the mountains. The entire world was the drip, drip of water in the overhanging trees and the softly terrifying sounds of creatures unseen moving in the shadows.

“These are the Raven Queen’s watchers here,” Lucan said, looking up into the tangled canopy. Remy couldn’t even see the birds he was seeing, and even if he could have seen them, he wasn’t entirely sure about the differences between crows and ravens. “They are less willing to speak to me. The Queen, they think, is unhappy with our errand.”

“Why would that old bitch care about what we do?” Paelias spat off the road into still black water. “She’ll get her share of dead whether we ever see Karga Kul or not.”

“The Raven Queen has never concerned herself with getting enough,” Biri-Daar said. “For her, the only enough is everything. Every life we save is an affront to her.”

“Then let’s make sure we do enough killing to keep her happy before we start saving all those lives,” Kithri said, so brightly her voice was almost a chirp.

“The ravens say one thing,” Lucan added. “Ahead, the dead things buried under the road are not always dead.” He paused, listening. “And the live things are in commerce with the dead.”

Keverel, in a humorless mood, made a warding gesture. “Must the crows speak in riddles?”

The ravens cawed back and forth to each other. “Ravens speak the way ravens speak,” Lucan said with a shrug. “You don’t have to listen. They also said that in another mile or so,

we were going to have to learn to swim. Then they laughed.”

In another mile or so, the Crow Road subsided below still black water. It was still visible, as a ribbon of open water winding between impenetrable walls of jungle swamp on either side, but as far ahead as they could see it did not re-emerge from the water. The horses stopped at the water and would not go forward no matter how hard they were spurred or dragged. They dug in their hooves, eyes wild and rolling, until the party gave up and stood apart from their mounts at the water’s edge.

“So the crows tell jokes as well as riddles,” Keverel said.

“Ravens,” Lucan corrected him again. “But the same is true of crows.”

They stood watching each other and looking out over the water for a long moment. “Does anyone know how to charm a horse?” Paelias asked. No one laughed.

“The horses know better,” Lucan said. “Too bad we don’t.”

“The only way is forward,” Biri-Daar said. “If the horses will not go, we will go without them. Salvage as much of your gear as you can.”

They loaded themselves with what they could carry, then drew lots to see who would go out into the water first. Paelias won, or lost. “Cleric,” he said. “Bless me.”

Keverel did, calling the power of Erathis to protect the eladrin. “Now we will find out what power Erathis has,” Paelias said, and he took a step into the water. It was ankle deep. He took another. “I can still feel the road,” he said. He stepped farther out. After ten paces he was knee-deep. After ten paces more, still knee-deep.

“All right,” Biri-Daar said. “Anything that can’t get wet, stow it high. We walk until we have to swim, and then we’ll see what happens.”

“Easy for you to say,” Kithri said. But she stepped into the water right after Paelias, and swallowed her pride when she needed to be lifted onto Biri-Daar’s shoulders as the water grew slowly but inexorably deeper.

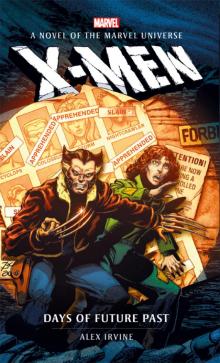

Marvel Novels--X-Men

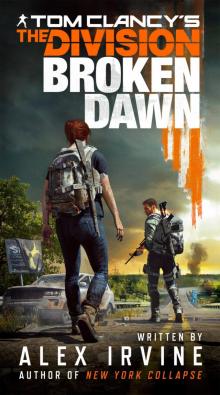

Marvel Novels--X-Men Tom Clancy's the Division

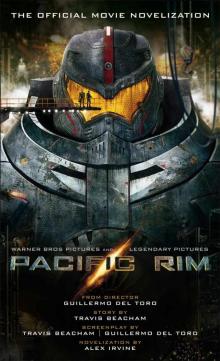

Tom Clancy's the Division Pacific Rim: The Official Movie Novelization

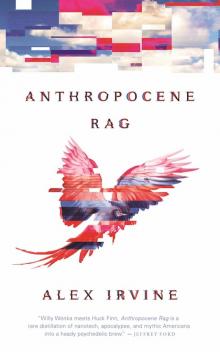

Pacific Rim: The Official Movie Novelization Anthropocene Rag

Anthropocene Rag Black Lagoon

Black Lagoon Phase One: The Incredible Hulk

Phase One: The Incredible Hulk Phase One: Iron Man

Phase One: Iron Man Pacific Rim

Pacific Rim Pacific Rim Uprising--Official Movie Novelization

Pacific Rim Uprising--Official Movie Novelization Phase Three: Marvel's Captain America: Civil War

Phase Three: Marvel's Captain America: Civil War Phase One: Thor

Phase One: Thor Dawn of the Planet of the Apes: The Official Movie Novelization

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes: The Official Movie Novelization Phase One: Marvel's The Avengers

Phase One: Marvel's The Avengers Phase One: Captain America

Phase One: Captain America Exiles

Exiles The Seal of Karga Kul: A Dungeons & Dragons Novel

The Seal of Karga Kul: A Dungeons & Dragons Novel Marvel's Ant-Man - Phase Two

Marvel's Ant-Man - Phase Two The seal of Karga Kul (dungeons and dragons)

The seal of Karga Kul (dungeons and dragons) Mare Ultima

Mare Ultima Phase Three: MARVEL's Doctor Strange

Phase Three: MARVEL's Doctor Strange MARVEL SUPER HEROES SECRET WARS

MARVEL SUPER HEROES SECRET WARS Phase Three: MARVEL's Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2

Phase Three: MARVEL's Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 Dawn of the Planet of the Apes

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes Independence Day: Resurgence: The Official Movie Novelization

Independence Day: Resurgence: The Official Movie Novelization